Currently Empty: ₹0.00

The Hiker, the Fire and the Shortest Path: Nurturing Gifted Thinkers

In school, math is often about speed: who can get the right answer fastest? But real mathematics is about patience. In GenWise’s online programs, we give students problems that are worth wrestling with. This blog documents the opening of a geometry course taught by Vidhya Govindan, where a simple question about shortest path problem for kids turned into a two-week journey of discovery. This is what happens when you prioritize thinking over answering.

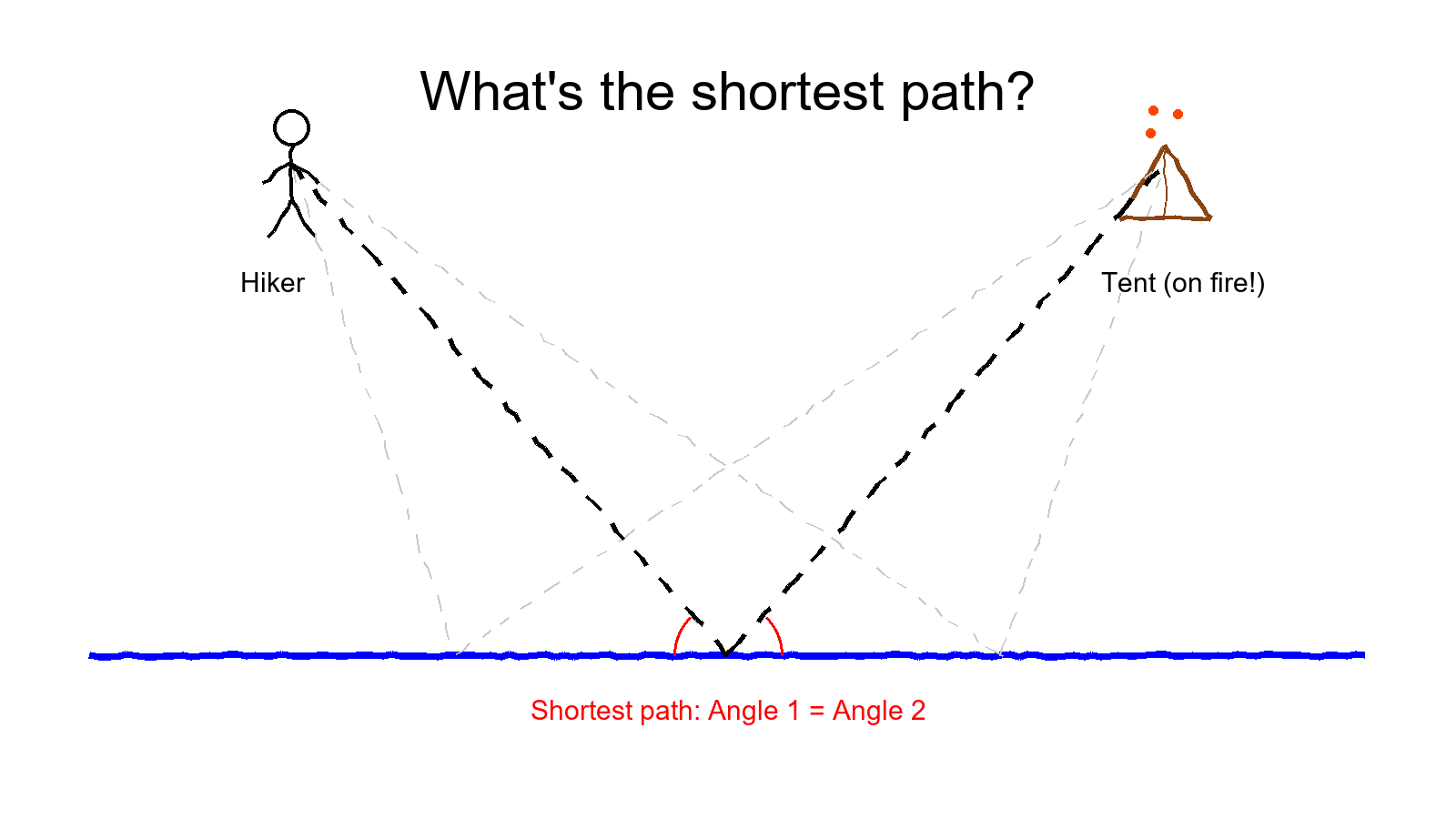

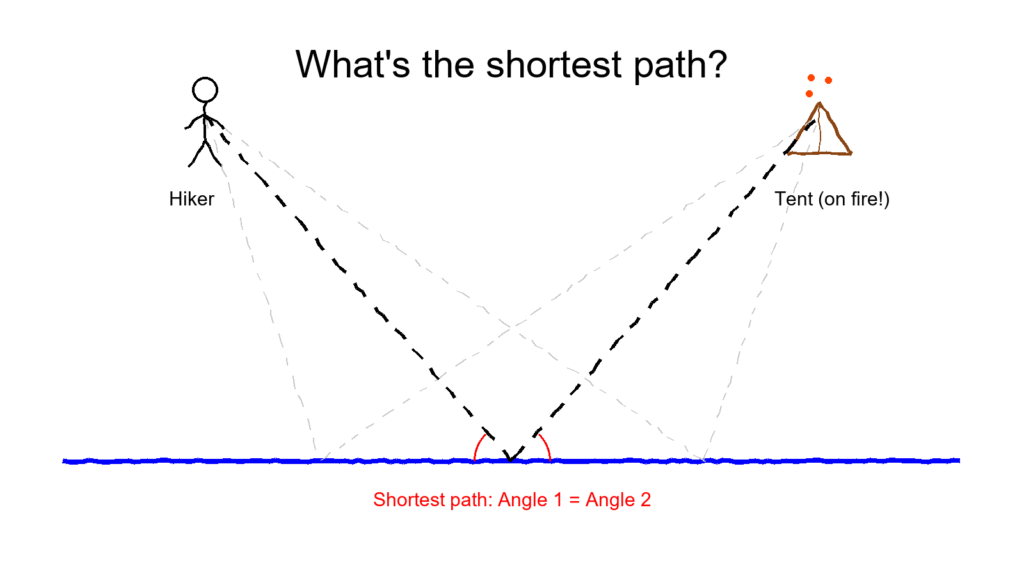

A hiker is out camping, some distance from his campsite. He suddenly sees that his tent is on fire. There’s a river nearby, running parallel to the line between him and the tent. He needs to run to the river, fill the bucket he carries, and run to the tent to put the fire out. What’s the shortest path he can take?

Try it yourself before reading on. Where on the river should he stop?

Most people’s instinct is to go to the nearest point on the river. It feels efficient. It feels logical.

It is also wrong.

The Intuitive Trap

When Vidhya presented this problem to nine middle schoolers, they fell into the same trap. “Just go straight to the river,” they said. It seemed obvious.

Instead of correcting them, Vidhya gave them the tools to prove themselves wrong. She provided a scalable diagram and a list of different points on the river. “Don’t guess,” she said. “Measure.”

The students measured the total distance for each point. They recorded the data. They built tables. And as the numbers came in, the “obvious” answer fell apart. The data showed a clear minimum distance at a specific point—but it wasn’t the one they had guessed.

Ayansh, one of the students, plotted the values in GeoGebra and saw the curve. The minimum was undeniable. But seeing the answer isn’t the same as understanding it. Why was that specific point the shortest?

Then someone noticed the angles. At the point where the total distance was shortest, the angle at which the hiker approached the river equaled the angle at which he left it.

Prisha jumped out of the math context entirely. “Like the incident ray and angle of reflection!” she said. She was describing the physics of light—in a geometry class. Nobody had told her to think about mirrors. She had connected the dots herself.

The Struggle is the Point

Identifying the property—equal angles—was a breakthrough. But it wasn’t the solution. How do you actually find that point on a piece of paper using just a ruler and compass?

Vidhya sent them home with that question. She didn’t give them the answer key; she gave them a sequence of guided questions to help them build the logic.

They struggled. And that was the plan.

When they returned for the second session, they weren’t just reciting a formula they’d memorized. They were wrestling with the logic.

Himank was honest about his experience: “I tried doing it, it took me a lot of time, and I was not actually able to do it.”

Arnold added, “It was a little bit confusing, I haven’t fully completed it yet.”

In a standard classroom, this might be seen as a failure of instruction. Here, it was a success of curriculum. The students were hitting the limit of their intuition and realizing they needed a more robust method. They were ready to learn because they had felt the need for the knowledge.

From Instinct to Insight

Vidhya guided them through the geometry. If you reflect the hiker’s starting position across the river (the line of reflection) and draw a straight line from that “mirror hiker” to the tent, the line crosses the river exactly at the perfect spot.

Suddenly, the “mirror” connection Prisha had made earlier wasn’t just a metaphor. It was the geometric key to the solution.

Once they unlocked that, the floodgates opened. They didn’t just solve the hiker problem; they started extending it.

What if the hiker has to stop at the river and a pasture before reaching the tent?

What if the hiker walks slower after picking up water from the river because of the weight of the bucket?

Problem solving is addictive. Students who had been stuck earlier were now racing ahead.

Aditya, reflecting on the course later, described the shift in his mindset: “The mentality goes from ‘I have to follow great people’ to ‘I have to question great people, try, find alternatives, find a more efficient way.'”

The Long Game

It took two 90 minute sessions and a meaningful struggle to solve a problem that could have been explained in five minutes.

But if Vidhya had just given them the formula on day one, they would have learned how to plug in numbers. By letting them wrestle with it, they learned something far more important: that their first instinct isn’t always right, that mathematics connects to physics in beautiful ways, and that a problem that seems impossible at first can yield to patience and logic.

Advaiy, looking back at the hiker problem weeks later, said: “It was so fascinating, because I thought there was no way you could figure it out.”

He could. It just took longer than a class period, and the scaffolding provided by a great mentor.

This approach is central to Gifted World’s Talent Nurturing Program, where we prioritize depth over speed. Vidhya Govindan teaches geometry and mathematical thinking to middle schoolers, helping them transition from following recipes to cooking up their own theories.